Durant, Will - A00036

"If we have never been amazed by the very fact that we exist, we are squandering the greatest fact of all."

8888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

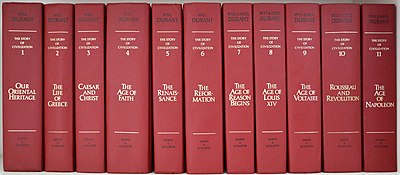

Will Durant and Ariel Durant (respectively, born Nov. 5, 1885, North Adams, Mass., U.S.—died Nov. 7, 1981, Los Angeles, Calif.; born May 10, 1898, Prosurov, Russia—died Oct. 25, 1981, Los Angeles) were American husband-and-wife writing collaborators whose Story of Civilization, 11 vol. (1935–75), established them among the best-known writers of popular philosophy and history.

Will Durant’s writing career began with the publication of Philosophy and the Social Problem (1917). His second book, The Story of Philosophy (1926), sold more than two million copies in less than three decades and was translated into several languages. The following year his only novel, Transition, appeared. It is largely an autobiographical account of his own early social, religious, and political disillusionments. In 1970 Durant published Interpretations of Life: A Survey of Contemporary Literature. This work, an expansion of the notes of a lifetime of reading modern literature, is informal and anecdotal and is aimed at the general reader.

In 1913, while teaching at the Ferrer Modern School in New York City, Durant married one of his pupils, Ada (or Ida) Kaufman, whom he called Ariel; she later adopted the name legally. Though she had been involved in the writing of every volume of The Story of Civilization, Ariel Durant was not given formal recognition as Will Durant’s collaborator until 1961, with publication of the seventh volume, The Age of Reason Begins. She continued as coauthor with her husband of the subsequent volumes in the series, including the Pulitzer Prize-winning 10th volume, Rousseau and Revolution (1967). They described their work together in A Dual Autobiography (1977).

8888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

HISTORIAN WILL DURANT DIES

HISTORIAN WILL DURANT DIES; AUTHOR OF 'CIVILIZATION' SERIES

Will Durant, a historian and philosopher who won a Pulitzer Prize with his wife, Ariel, for a volume of their ''Story of Civilization,'' died late yesterday. He was 96 years old.

A spokesman for Cedars-Sinai Hospital here confirmed that Mr. Durant died of heart failure about 11 P.M., apparently without ever learning that his wife had died Oct. 25 at 83. News of her death was kept from Mr. Durant, who had been under intensive care for three weeks after surgery.

---- Seeker of Total Picture

One day in 1912, as he lay ill with dysentery in Damascus, 27-yearold Will Durant conceived ''The Story of Civilization.'' He did not get around to starting it until 1927, but when it was completed in 1975, it packaged more than 110 centuries of human history in 11 volumes.

Dr. Durant's inspiration was the 19th-century British historian Henry Thomas Buckle, who wrote ''An Introduction to the History of Civilization'' but died in Damascus in 1862 before he was able to continue the history itself.

Advertisement

Dr. Durant's design, he said later, was ''to tell as much as I can, in as little space as I can, of the contribution that genius and labor have made to the cultural heritage of mankind.''

''It may be of some use,'' he went on, ''to those upon whom the passion for philosophy has laid the compulsion to try to see things whole, to pursue perspective, unity and understanding through history in time.''

The aim, he said, is ''to portray in each period the total complex of a nation's culture, institutions, adventures and ways.'' Published in 1935, the first volume, ''Our Oriental Heritage,'' traced the beginnings of man and the story of Eastern civilization. The 10th volume, ''Rousseau and Revolution,'' brought the chronicle up to the dawn of the 19th century.

With the publication of the 10th volume, Dr. Durant, then 81, and his 69-year-old wife had planned to leave the next two centuries to ''fresher spirits.''

But in 1975, in the week of Dr. Durant's 90th birthday, they released ''The Age of Napoleon.'' Two years later, they announced the publication of a joint work, ''A Dual Biography,'' on their own lives. Won Pulitzer Prize

Advertisement

''Rousseau and Revolution,'' which won the Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction in 1968 and was a Book-of-the-Month Club choice, was a best-seller, as were the 10 other volumes. This meant total sales of more than two million copies in nine languages, a readership enjoyed by few historians. Even Arnold J. Toynbee, whose 120-volume ''A Study of History'' rivaled Dr. Durant's in bulk, did not attain such popularity.

One explanation for the success of ''The Story of Civilization'' was the clarity and wit of its prose. Another was its emphasis on man's achievements in art, literature, science and philosophy rather than on the follies and crimes of mankind or on military, political and economic events.

''History,'' Dr. Durant and his wife once remarked, ''is above all else the creation and recording of the intellectual, moral and aesthetic heritage of mankind; progress is the increasing abundance, use, preservation and transmission of that heritage.

''To those of us who study history not merely as a warning reminder of man's follies and crimes but also as a remembrance of generative souls, the past ceases to be a depressing chamber of horrors; it becomes a celestial city, a spacious country of the mind, wherein a thousand saints, statesmen, inventors, scientists, poets, artists, musicians, philosophers and lovers still live and speak, teach and carve and sing.'' Approach Criticized

Dr. Durant's approach to history was looked down on by many serious historians. The late Crane Brinton of Harvard wrote of ''The Age of Voltaire,'' the ninth volume in the Durants' series:

''It is difficult for a professor of history to say good things about their work without seeming to unbend, if not to patronize. Clearly they are readable. They can produce the telling anecdote, the picturesque detail, the sense of movement in events and ideas, though they cannot create the kind of dramatic suspense Barbara Tuchman achieved in her 'Guns of August.'

Advertisement

''Above all, though, they are often mildly epigramatic. Though they can be comfortably realistic about human nature, the Durants are never uncomfortably realistic, never daring, never surprising. Theirs is the enlightenment that still enlightens, basically kindly, hopeful, progressive, reasonable, democratic.''

Other critics said Dr. Durant sought to personify processes and events, a charge to which he admitted. ''We believe that in the last hundred years history has been too depersonalized,'' he once said, ''and that statistics have replaced men in the story of mankind. History operates in events but through persons; these are the voice of events, the flesh and blood upon which events fall, and the human responses and feelings are also history.'' 'Popularizing' Denied

But he denied that he was a ''popularizer,'' asserting in a chiding letter to Time magazine in 1939: ''I really have no thought of 'popularizing' history in the sense of oversimplifying it for simple minds. I have merely applied to the writing of a history of civilization that moral obligation to be intelligible which is part of the French tradition in all fields of literature, even in philosophy.

''It is the curse of my life that minds accustomed to German obscurity have come to take it for granted that anything that is clearly expressed must be superficial.''

The economic freedom for years of work on ''The Story of Civilization'' was provided by ''The Story of Philosophy,'' Dr. Durant's first book. A one-volume account of the ideas of the world's greatest thinkers, it was published in 1926 and over the years sold three milion copies.

Advertisement

''Like other private events in my life,'' Dr. Durant once recalled, ''it was pure accident. I had given up my youthful ideas of becoming an author and was running an adult education school in New York, working 16 hours a day.''

In 1925, he said, Emanuel Haldeman-Julius, who published ''little 5-cent books on virtually every subject under the sun,'' noticed that he was lecturing on Plato and came in to listen. Lecture Became Booklet

''Had he passed by 20 minutes earlier or later he probably would not have stopped,'' Dr. Durant said. ''But he did stop, and later wrote me, asking me to type out the lecture for one of his little books. I was too busy. He insisted and sent me an advance check for $150.

''I could refuse neither his courage nor his check. Sometime later he sent me another check for a booklet on Aristotle. Before long there were 11 such booklets.''

These ''Little Blue Books'' came to the attention of M. Lincoln Schuster, who put them together into ''The Story of Philosophy.'' Simon & Schuster was also the publisher of ''The Story of Civilization'' and from both publications made a steady and substantial income.

Advertisement

There was little in Dr. Durant's early life to foreshadow his future interest in history. Born Nov. 5, 1885, in North Adams, Mass., he was one of 11 children of Joseph and Marie Allors Durant, French-Canadian immigrants.

Intended by his parents for the Roman Catholic priesthood, he went to St. Peter's College in New Jersey, from which he graduated in 1907. His dedication to theology was sufficiently weakened at school for him to be attracted to journalism and a two-month summer job at The New York Evening Journal. In the fall he began to teach Latin, French, Greek and geometry at Seton Hall college in South Orange, N.J., and two years later he entered the seminary there. Withdrew From Seminary

''It was for me,'' he wrote in a 1927 memoir, ''an act of hypocrisy, generosity, idealism and egotism. After two years of effort I had not had success in recapturing either the old piety or the old faith.''

Instead, he discovered Spinoza's ''Ethics,'' which reinforced his heretical doubts to the point that he withdrew from the seminary. Shortly afterward he was excommunicated.

He then moved into New York's radical circles, becoming a teacher at the anarchist-sponsored Francisco Ferrer School. There, after returning from a trip abroad financed by a wealthy patron of the arts, he met Ida Kaufman, a 14-year-old pupil.

Advertisement

''She was sprightly and gay and impish so I called her Puck,'' Dr. Durant recalled in later years. ''I fell in love with her and kidnapped her and married her.''

''I was his tabula rasa,'' Mrs. Durant said. ''I was blank. He could write from the beginning. I became the ears that listened to him, and later, I hope, something more.''

She was 15 at her marriage on Oct. 31, 1913, and came to the ceremony with her roller skates slung over her shoulder. Her husband was just about to turn 28. He called her Ariel, after the the imp in Shakespeare's ''The Tempest,'' and she later had her name legally changed.

After their marriage, Dr. Durant became director of the Labor Temple School, an adult education center where he taught philosophy and history to workers until 1927. At the same time he and his wife attended Columbia University, and he received a doctorate in philosophy in 1917.

The couple had a daughter, Ethel, and adopted a son, Louis. Spiced With Anecdotes

Although he had published his dissertation, ''Philosophy and the Social Problem,'' in 1917, Dr. Durant did not achieve wide recognition until ''The Story of Philosophy'' came out. The book was a survey of philosophy, from Plato to John Dewey, aimed at the general reader. It was spiced with anecdotes and personal comments, and it was eminently readable.

Advertisement

Dr. Durant followed its success with ''Transition,'' an autobiographical novel, and ''Mansions of Philosophy: A Survey Of Human Life and Destiny,'' which covered such topics as logic, metaphysics, theology, esthetics, morality, political theory and philosophy of history.

Out of a trip to the Far East came ''Case for India,'' an indictment of British imperialism there. In demand as an essayist and oracle, Dr. Durant produced a number of articles on education and psychology that were bound together in ''Adventures in Genius'' and ''Program for Americans.'' He also traveled to the Soviet Union and concluded in ''Tragedy of Russia'' in 1933 that the country was ''a gigantic prison.''

Meantime, he and his wife began their long collaboration on ''The Story of Civilization.'' In the first books Mrs. Durant provided much of the research, but her role increased to that of partnership and her name appeared as co-author starting with the seventh volume.

In their Spanish-style home in Hollywood Hills, the couple prepared each volume by scanning 500 books, mostly secondary sources, jotting down citations on green slips and significant ideas and comments on white pads. Notes on a Rocking Chair

The notes were then strung in order beside a drafting board resting across the arms of Dr. Durant's rocking chair. There, he consulted the notes and reference materials and wrote his daily wordage in a notebook to be typed later.

Advertisement

''The Story of Civilization'' became a way of life for the Durants. Most of the time they put in seven days a week, from 8 in the morning to 10 at night, and it took about four years to produce a book.

Thus, after ''Our Oriental Heritage'' came ''The Life of Greece'' in 1939, ''Caesar and Christ'' in 1944, ''The Age of Faith'' in 1950, ''The Renaissance'' in 1953, ''The Reformation'' in 1957, ''The Age of Reason Begins'' in 1961, ''The Age of Louis XIV'' in 1963, ''The Age of Voltaire'' in 1965, ''Rousseau and Revolution'' in 1967 and, finally, ''The Age of Napoleon.''

''The enterprise gave unity to our lives, and a meaning to each day,'' the couple told a friend in 1968. ''We have never felt it was a burden. It was a joy even in its mechanical aspects, for at each stage we had the beaver's pleasure in seeing the structure rise.'' Studded With Aphorisms

Dr. Durant studded ''The Lessons of History,'' which followed ''Rousseau and Revolution'' and distilled the couple's observations, with aphorisms, including these:

- ''The first biological lesson of history is that life is competition. Competition is not only the life of trade, it is the trade of life - peaceful when food abounds, violent when the mouths outrun the food.''

- ''History offers some consolations by reminding us that sin has flourished in every age. Man has never reconciled himself to the Ten Commandments.''

- ''Democracy is the most difficult of all forms of government, since it requires the widest spread of intelligence, and we forgot to make ourselves intelligent when we made ourselves sovereign.'' Optimistic to the End

Dr. Durant consistently took a generally optimistic view of civilization, despite a growing belief that ''the world situation is all fouled up.''

Advertisement

''Civilization is a stream with banks,'' he said in his precise voice. ''The stream is sometimes filled with blood from people killing, stealing, shouting and doing the things historians usually record, while on the banks, unnoticed, people build homes, make love, raise children, sing songs, write poetry and even whittle statues.

''The story of civilization is the story of what happened on the banks. Historians are pessimists because they ignore the banks for the river.''

8888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

William James Durant (/dəˈrænt/; November 5, 1885 – November 7, 1981) was an American historian and philosopher, best known for his 11-volume work, The Story of Civilization, which contains and details the history of Eastern and Western civilizations. It was written in collaboration with his wife, Ariel Durant, and published between 1935 and 1975. He was earlier noted for The Story of Philosophy (1926), described as "a groundbreaking work that helped to popularize philosophy".[1]

Durant conceived of philosophy as total perspective or seeing things sub specie totius (i.e., "from the perspective of the whole")—a phrase inspired by Spinoza's sub specie aeternitatis, roughly meaning "from the perspective of the eternal".[2] He sought to unify and humanize the great body of historical knowledge, which had grown voluminous and become fragmented into esoteric specialties, and to vitalize it for contemporary application.[3] As a result of their success, he and his wife were jointly awarded the Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction in 1968 and the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1977.

Early life

[edit]William James Durant was born in North Adams, Massachusetts, to French-Canadian Catholic parents, Joseph Durant and Mary Allard, who had been part of the Quebec emigration to the United States.[4][5]

After graduating from St. Peter's Preparatory School in Jersey City, New Jersey, in 1903, Durant enrolled at Saint Peter's College (now Saint Peter's University), also in Jersey City, where he graduated in 1907.[6] Historian Joan Rubin writes of that period, "Despite some adolescent flirtations, he began preparing for the vocation that promised to realize his mother's fondest hopes for him: the priesthood. In that way, one might argue, he embarked on a course that, while distant from Yale's or Columbia's apprenticeships in gentility, offered equivalent cultural authority within his own milieu."[7]

In 1905, he began experimenting with socialist philosophy, but, after World War I, he began recognizing that a "lust for power" underlay all forms of political behavior.[7] However, even before the war, "other aspects of his sensibility had competed with his radical leanings," notes Rubin. She adds that "the most concrete of those was a persistent penchant for philosophy. With his energy invested in Baruch Spinoza, he made little room for the Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin. From then on, writes Rubin, "his retention of a model of selfhood predicated on discipline made him unsympathetic to anarchist injunctions to 'be yourself.'... To be one's 'deliberate self,' he explained, meant to 'rise above' the impulse to 'become the slaves of our passions' and instead to act with 'courageous devotion' to a moral cause."[7]

Teaching career

[edit]

From 1907 to 1911, Durant taught Latin and French at Seton Hall University in South Orange, New Jersey.[5]

After leaving Seton Hall, Durant was a teacher at Ferrer Modern School from 1911 to 1913.[5] Ferrer was "an experiment in libertarian education," according to the Who's Who of Pulitzer Prize Winners.[5] Alden Freeman, a supporter of the Ferrer Modern School, sponsored him for a tour of Europe.[8]

In 1913, he resigned his post as teacher and married the 15-year-old Ariel Kaufman; they had one daughter, Ethel, and a "foster" son, Louis, whose mother was Flora—Ariel's sister.[5] To support themselves, he began lecturing in a Presbyterian church for $5 and $10; the material for the lectures became the starting point for The Story of Civilization.

By 1914, he began to reject "intimations of human evil," notes Rubin, and to "retreat from radical social change." She summarizes the changes in his overall philosophy:

Durant was director and lecturer at the Labor Temple School in New York City from 1914 to 1927 while pursuing a PhD at Columbia University that he completed in 1917, the year he also served as an instructor in philosophy.[5]

Writing career

[edit]In 1908, Durant worked as a reporter for Arthur Brisbane's New York Evening Journal.[5] At the Evening Journal, he wrote several articles on sexual criminals.

In 1917, while working on a doctorate in philosophy at Columbia University, he wrote his first book, Philosophy and the Social Problem. He discussed the idea that philosophy had not grown because it had refused to confront the actual problems of society. He received his doctorate from Columbia that same year.[9] He was also an instructor at the university.

The Story of Philosophy

[edit]The Story of Philosophy originated as a series of Little Blue Books (educational pamphlets aimed at workers) and because it was so popular, it was republished as a hardcover book by Simon & Schuster in 1926[10] and became a bestseller, giving the Durants the financial independence that allowed them to travel the world several times and spend four decades writing The Story of Civilization. Will left teaching and began work on the 11-volume Story of Civilization.

The Story of Civilization

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2024) |

Throughout their writing of The Story of Civilization, the Durants strove to create what they called "integral history."[This quote needs a citation] They opposed the "specialization" of history, an anticipatory rejection of what some have called[weasel words] the "cult of the expert."[This quote needs a citation] Their goal was to write a biography of a civilization, in this case, the history of the West; not only would it describe the usual history of the Western world's wars, the history of politics and biographies of people of greatness and villainy, but also the history of the Western world's culture, art, philosophy, religion, and the rise of mass communication.[citation needed] Much of The Story considers the living conditions of everyday people throughout the 2500-year period that their "story" of the West covers, and bring an unabashedly moral framework to their accounts,[citation needed] constantly stressing the "dominance of the strong over the weak, the dominance of the clever over the simple."[This quote needs a citation] As of this date,[when?]The Story of Civilization is the most successful historiographical series ever written.[according to whom?] In the 1990s, an unabridged audiobook production of all 11 volumes was produced by Books On Tape, read by Grover Gardner (under the alias Alexander Adams).[citation needed]

The Durants were awarded the Pulitzer Prize for literature for Rousseau and Revolution (1967), the 10th volume of The Story of Civilization.[citation needed] In 1977, it was followed by one of the highest awards was ever granted to civilians by the United States government, the Presidential Medal of Freedom (awarded by President Gerald Ford).[citation needed] As well, the Durants received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement in 1976.[11]

Other works

[edit]

On April 8, 1944, Durant was approached by two leaders of the Jewish and Christian faiths, Meyer David and Christian Richard, about starting "a movement, to raise moral standards." He suggested instead that they start a movement against racial intolerance and outlined his ideas for a "Declaration of Interdependence". The movement for the declaration, Declaration of INTERdependence, Inc., was launched at a gala dinner at the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel on March 22, 1945, attended by over 400 people including Thomas Mann and Bette Davis.[12] The Declaration was read into the Congressional Record on October 1, 1945, by Ellis E. Patterson.[13][a]

Throughout his career, Durant made several speeches, including "Persia in the History of Civilization", which was presented as an address before the Iran-America Society in Tehran, Iran, on April 21, 1948, and it had been intended for inclusion in the Bulletin of the Asia Institute (formerly, the Bulletin of the American Institute for Persian, then Iranian, Art and Archaeology), Vol. VII, no. 2, which never saw publication.[14]

Rousseau and Revolution was followed by a slender volume of observations which was titled The Lessons of History, which was both a synopsis of the series as well as an analysis of human history.

Though Ariel and Will had intended to carry the work on The Story of Civilization into the 20th century, at their now very advanced age, they expected the 10th volume to be their last. However, they went on to publish a final volume, their 11th, The Age of Napoleon in 1975. They also left notes behind for a 12th volume, The Age of Darwin, as well as an outline of a 13th volume, The Age of Einstein, which would have taken The Story of Civilization to 1945.

Three posthumous works by Durant have been published in recent years, The Greatest Minds and Ideas of All Time (2002), Heroes of History: A Brief History of Civilization from Ancient Times to the Dawn of the Modern Age (2001) and Fallen Leaves (2014).

Final years

[edit]The Durants shared an intense love for one another as they explained in their Dual Autobiography. After Will entered the hospital, Ariel stopped eating, and she died on October 25, 1981. Though their daughter, Ethel, and their grandchildren strove to conceal the news of Ariel's death from the ailing Will, he found out that she had died while he was watching the evening news, and he died two weeks later, two days after his 96th birthday, on November 7, 1981. Will was buried beside Ariel in the Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery, in Los Angeles.

Writing about Russia

[edit]In 1933, he published Tragedy of Russia: Impressions from a Brief Visit and soon afterward, he published The Lesson of Russia. A few years after the books were published, the social commentator Will Rogers read them and he described a symposium which he had attended which included Durant as one of the contributors to it. He later wrote of Durant, "He is just about our best writer on Russia. He is the most fearless writer that has been there. He tells you just what it's like. He makes a mighty fine talk. One of the most interesting lecturers we have, and a fine fellow."[1]

Writing about India

[edit]In 1930, Durant visited British India to collect information for The Story of Civilization. While in India, Durant was shocked by the poverty and instances of starvation he witnessed, to the point where he took a period of time off from his intended goal to write a short book titled The Case for India about the "conscious and deliberate bleeding of India" by Britain.[15] He also stated that "I began to feel that I had come upon the greatest crime in all history." when learning of the plight of India.[16][17] In The Case for India, Durant wrote that "The British conquest of India was the invasion and destruction of a high civilization by a trading company utterly without scruple or principle, careless of art and greedy of gain, over-running with fire and sword a country temporarily disordered and helpless, bribing and murdering, annexing and stealing, and beginning their career of illegal and 'legal' plunder which has now gone on ruthlessly for one hundred and seventy-three years."[18]

Personal views

[edit]On his personal religious beliefs, Durant wrote that “I am prepared to have you put me down as an atheist, since I have reluctantly abandoned belief in a personal and loving God. But I am loath to leave the word God out of my life and creed.”, adding that he was “a Christian in the literal and difficult sense of sincerely admiring the personality of Christ and making a persistent effort to behave like a Christian.”[19]

Reception

[edit]

While Durant's work was well received by popular audiences, its academic reception was more critical. Classics scholar Moses Finley criticised Durant's The Life of Greece on a number of grounds, including the book's racial essentialism and support for the great man theory of history.[20]

Selected bibliography

[edit]Will Durant's full bibliography can be found online.[21]

- 1917. Philosophy and the Social Problem. New York: Macmillan.

- 1926. The Story of Philosophy. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1927. Transition. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1929. The Mansions of Philosophy. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1930. The Case for India. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1931. A Program for America. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1931. Adventures in Genius. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1932. On the Meaning of Life. New York: Ray Long and Richard R. Smith.

- 1933. The Tragedy of Russia: Impressions From a Brief Visit. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1936. The Foundations of Civilisation. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1953. The Pleasures of Philosophy. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1968. (with Ariel Durant) The Lessons of History. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1970. (with Ariel Durant) Interpretations of Life. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1977. (with Ariel Durant) A Dual Autobiography. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 2001. Heroes of History: A Brief History of Civilization from Ancient Times to the Dawn of the Modern Age. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 2002. The Greatest Minds and Ideas of All Time. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 2003. An Invitation to Philosophy: Essays and Talks on the Love of Wisdom. Promethean Press.

- 2008. Adventures in Philosophy. Promethean Press.

- 2014. Fallen Leaves. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Little Blue Books contributions

[edit]- 1922. A Guide to Plato. Girard, Kansas: Haldeman-Julius Company.

- 1922. The Story of Aristotle's Philosophy. Girard, Kansas: Haldeman-Julius Company.

- 1923. A Guide to Francis Bacon. Girard, Kansas: Haldeman-Julius Company.

- 1924: A Guide to Schopenhauer. Girard, Kansas: Haldeman-Julius Company.

- 1924. A Guide to Spinoza. Girard, Kansas: Haldeman-Julius Company.

- 1924. The Philosophy of Immanuel Kant. Girard, Kansas: Haldeman-Julius Company.

- 1924. The Story of Friedrich Nietzsche's Philosophy. Girard, Kansas: Haldeman-Julius Company.

- 1924. Voltaire and the French Enlightenment. Girard, Kansas: Haldeman-Julius Company.

- 1925. Anatole France: The Man and His Work. Girard, Kansas: Haldeman-Julius Company.

- 1925. Contemporary American Philosophers: Santayana, James and Dewey. Girard, Kansas: Haldeman-Julius Company.

- 1925. Contemporary European Philosophers: Bergson, Croce and Bertrand Russell. Girard, Kansas: Haldeman-Julius Company.

- 1925. The Philosophy of Herbert Spencer. Girard, Kansas: Haldeman-Julius Company.

- 1928. (with Clarence Darrow) Are We Machines? Girard, Kansas: Haldeman-Julius Company.

- 1935. Our Oriental Heritage. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1939. The Life of Greece. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1944. Caesar and Christ. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1950. The Age of Faith. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1953. The Renaissance. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1957. The Reformation. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1961. (with Ariel Durant) The Age of Reason Begins. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1963. (with Ariel Durant) The Age of Louis XIV. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1965. (with Ariel Durant) The Age of Voltaire. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1967. (with Ariel Durant) Rousseau and Revolution. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1975. (with Ariel Durant) The Age of Napoleon. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Rogers, Will (1966). Gragert, Steven K. (ed.). The Papers of Will Rogers. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 393.[dubious – discuss] The details of this book appear to be wrong – see talk page

- ^ Durant, Will. "What is Philosophy?". Archived from the original on December 28, 2010.

- ^ Durant, Will (1935). Our Oriental Heritage. Simon & Schuster. p. vii.

- ^ "Will Durant". Freedom From Religion Foundation. November 5, 1980. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g Brennan, Elizabeth A.; Clarage, Elizabeth C. (1999). Who's Who of Pulitzer Prize Winners. Phoenix: Oryx Press. p. 257. ISBN 1-57356-111-8. OCLC 750569323 – via Google Books.

- ^ "The will to capture history". Hudson Reporter. November 4, 2010. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Rubin, Joan Shelley. The Making of Middlebrow Culture, University of North Carolina Press (1992).

- ^ Durant, Will (1935). Our Oriental Heritage. Simon & Schuster. p. 1051.

- ^ Norton, Dan (Spring 2011), "A Symphony of History: Will Durant's The Story of Civilization", The Objective Standard, 6 (1), 3rd paragraph, retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ WUACC, archived from the original on March 10, 2007.

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ a b Interdependence, Will Durant Foundation, archived from the original on March 10, 2012.

- ^ Declaration (PDF), Will Durant foundation, archived from the original (PDF) on December 18, 2011.

- ^ Durant, Will. "Persia in the History of Civilization" (PDF). Addressing Iran-America Society. Mazda Publishers. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 23, 2011.

- ^ Tharoor, Shashi, (2019). Inglorious Empire: What the British Did to India. Minneapolis, Minnesota, Scribe Publications, pg. 1

- ^ "When a U.S. Historian Called British Rule In Bharat 'The Greatest Crime In All History'". hindupost.in. March 7, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

- ^ Balakrishna, Sandeep (March 15, 2019). "A Case for India: A Glimpse into how the British Plundered India and Destroyed a Great Civilisation". The Dharma Dispatch. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

- ^ Durant, Will, (1930). The Case for India, New York City, Simon & Schuster, p. 7

- ^ "An Examined Life". America Magazine. May 6, 2015. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ "The Reviews Are In | Society for US Intellectual History". July 13, 2019. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ "Bibliography". Archived from the original on February 10, 2013.

888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

No comments:

Post a Comment